| Cat neutering practices in the UK |

go>> |

| Cats

and swine flu |

go>> |

| Cats and avian flu |

go>> |

| Tritrichomonas

foetus infection in cats |

go>> |

| Inherited problems

in cats |

go>> |

| Antifreeze

- the dangers to cats |

go>> |

| Working in

cat rescue - helpful information from Canada |

go>> |

Despite neutering being one of the most common veterinary procedures, questions remain about what constitutes best practice, and when is the ideal time to neuter. These were the focus of attention at a meeting of The Cat Group, held in London last September, to which representatives from the UK veterinary schools,and a number of other veterinary experts, were invited. This article presents a summary of the discussions.

click here...

At the beginning of November 2009, a sick 13-year old cat in Iowa, USA was diagnosed with the H1N1 ‘swine flu’ influenza virus. He had become lethargic, lost his appetite and had respiratory distress and diarrhoea. He was treated with antibiotics and fluids and recovered. This is the first report that cats can become infected with the swine flu virus.

It is very likely that the cat caught the virus from humans. Two of the three people who lived with the cat had flu-like symptoms before the cat became ill. Although H1N1 has not been confirmed as the cause of their illness, there is strong circumstantial evidence that they were the source of the infection and the virus was transmitted from them to the cat rather than the other way round, as the cat did not go outdoors.

There appears to be a small risk of animals catching the current swine flu virus from humans. Pigs, turkeys and pet ferrets have been diagnosed with the virus. Previously cats have died from eating birds infected with the earlier avian flu H5N1 virus.

However, there is no evidence yet that influenza viruses spread between cats or from cats to humans.

To reduce the risk of pet cats becoming infected from people with flu, the same precautions should be taken that apply to preventing human-to-human spread of the virus. Close contact with cats should be avoided, particularly face to face contact. Coughs and sneezes should be contained in paper tissues which should then be discarded hygienically. Hands should be washed very carefully before handling pets.

Cats in households in which people have symptoms of flu should be monitored carefully. If cats show signs of illness, owners should seek advice immediately from their veterinary surgeon.

For

further information, visit the websites below:

http://www.avma.org/public_health/influenza/new_virus/

http://www.catvets.com/newsroom/?Id=869

Health

Protection Agency http://www.hpa.org.uk

Department

for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairshttp://www.defra.gov.uk

Cats

have been identified as one of the species which can become infected

with the H5N1 avian flu virus. Natural infection almost certainly

occurs when cats eat infected birds, and fatal infections in cats

have been recorded in Germany and Austria. In laboratory studies

cats have been infected experimentally and have transmitted the

virus to other cats with which they were in contact. Recent

research, the results of which have yet to be confirmed, indicates

that in parts of south-east Asia, where poultry have been infected

with the virus, up to 20 per cent of cats have antibodies, suggesting

that many more cats become infected than become ill. This

raises the concern that cats might be a vehicle in which the virus

can become more addapted to mammals, and therefore spread readily

to man. However, there has been no evidence to date that cats

have been responsible for transmitting the virus to humans.

The simple and most effective way of avoiding cats being infected

is to keep them indoors, especially if they are known to wander

and are in an area where infected birds are known to be present.

When cases of H5N! infection occur in poultry in the UK, owners

within the 3 km protection zone should consider keeping their cats

indoors as recommended by DEFRA:

'As

a precautionary approach we recommend that if you live within

3km of a premises where avian influenza is confirmed (the protection

zone) pet owners should aim to keep their cats indoors and exercise

their dogs on a lead. This is for the protection of your animals

and is not for public health purposes. In all other areas you

should continue as normal and your pets are not at risk.'

Click

here for DEFRA's advice on avian flu and cats

Similarly,

a recent report form the European Commission Standing Committee

on the Food Chain and Animal Health says:

'Current

knowledge indicates that no H5N1 infection has ever occurred in

humans due to animals other than domestic poultry. Current knowledge

suggests that the disease in carnivores such as cats is a “cul

de sac” of the infection that has not lead to an increase

in the risk posed by this virus for animal or public health.

In

areas where H5N1 has been confirmed in wild birds:

- sick or dead cats and dogs that may have

had contacts with infected birds or their carcasses should undergo

veterinary inspection or post-mortem examination. When felt

necessary by the veterinarian and in accordance with the instructions

given by the veterinary authorities, further testing should

be carried out;

- contacts between domestic carnivores, particularly

cats, and wild birds should be prevented, i.e. cats should be

kept indoors and dogs should be kept on a leash or otherwise

restrained, and kept under control by the owner;

- where stray cats or dogs are found dead they

should not be touched and the veterinary authorities should

be informed, so that post-mortem examination and further testing

can be performed'

The

Cat Group urges pet owners not to panic and abandon or rehome their

cats because of fears of infection with bird flu.

This highly pathogenic virus first appeared in chickens in Hong Kong in 1997 and spread to people, with six deaths being recorded. In 2003 there were two further human deaths associated with infection by the same subtype of virus in southern China. Throughout 2004, H5N1 viruses spread throughout Southeast Asia resulting in the deaths, or slaughter of millions of chickens and over 30 people. To date, 167 human cases have been reported. The human infections were acquired directly from infected birds and fortunately the virus does not appear to spread between people.

However, a major threat from this new virus is that suddenly it might change and cause epidemics in people. This might occur if the virus mutated in chickens or recombined with existing human influenza viruses already in people or pigs, to produce novel viruses that could then spread readily from person to person, causing widespread disease. The World Health Organisation is closely monitoring the situation for the appearance of any such variant viruses in people.

Other concerns are that the H5N1 virus has been found to cause fatal disease in domestic cats, as well as in tigers and leopards in captivity, through the consumption of infected poultry meat; and the virus can spread between cats. Therefore there is a theoretical possibility that cats may be involved in natural history of these viruses, serving as a vehicle for the spread of the virus to other species, particularly man. Most authorities consider this outcome to be unlikely since previously reported disease in cats caused by avian influenza viruses have not been associated with widespread infection, or fatalities in cats. The first recorded natural, fatal infection of cats with an avian influenza virus was in Korea in 1942, but the subtype of that virus is not known. Since then there have been anecdotal accounts of natural feline infections in Thailand in 2004 and the transmission of a current H5N1 isolate from chickens to cats, and between cats, has been reported recently. It is considered even more unlikely that cats could act as a ‘mixing vessel' to generate recombinant influenza viruses, as might occur in people or pigs. Therefore, the risk that cats might pose should be kept in perspective.

Kuiken T, et al (2004) Avian H5N1 influenza in cats. Science 306 :241

Keawcharoen J, et al (2004) Avian influenza H5N1 in tigers and leopards. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10, 2189-2191 |

Question

& Answer

Can

cats bring avian flu into a household?

We have two indoor-outdoor cats which occasionally catch

rats or birds and, of course, bring them into the house. It doesn't

take much to imagine one's cat catching and bringing into the house

an infected, ill migratory bird. How concerned should pet owners

be? And what is a reasonable course of action under such circumstances?

The

advice from an eminent virologist and supported by DEFRA, the British

government department for the environment, food and rural affairs

is:

The facts

are that cats are susceptible to the current H5N1 strains of

avian flu virus, as are garden birds. Consequently, there

is a theoretical risk that cats could introduce the virus into a

household through predation, and that people could be infected from

the bird, or the cat. The risk must be considered remote. However,

in areas where bird flu has been identified it is recommended that

cats are kept indoors for their own protection.

Please

also see DEFRA's

guidance on the handling and disposing of dead garden and wild birds

The following

websites are also a useful source of information:

Advisory

Board on Cat Diseases (ABCD)

British

Veterinary Association (BVA)

Royal

Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB)

Tritrichomonas foetus is a microscopic single-celled flagellated protozoan parasite that has traditionally been identified as a cause of reproductive disease in cattle (infertility, abortion and endometritis). It has been found all over the world, but the widespread use of artificial insemination in breeding cattle has led to the virtual elimination of this organism from the cattle population in many countries including the UK and much of Europe.

There have been a number of recent studies, mostly form the USA, that have demonstrated that T foetus may also be an important cause of diarrhoea in cats. It can infect and colonises the large intestine, and can cause prolonged and intractable diarrhoea.

Studies have shown that this parasite mainly causes colitis (large bowel diarrhoea) with increased frequency of defaecation, semi-formed to liquid faeces, and sometimes fresh blood or mucus in the faeces. With severe diarrhoea the anus may become inflamed and painful, and in some cases the cats may develop faecal incontinence. Although cats of all ages can be affected with diarrhoea, it is most commonly seen in young cats and kittens, the majority being under 12 months of age. Most of the affected cats have come from rescue shelters and pedigree breeding colonies. Abdominal ultrasound examination may show corrugation of the large bowel and local lymphadenopathy. Colonic biopsies from affected cats typically show mild to severe inflammatory changes with infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells – a pattern commonly seen with other infectious agents and with inflammatory bowel disease. However, the parasites may be seen in close association with the mucosa. Although the diarrhoea may be persistent and severe, most affected cats are otherwise well, and show no significant weight loss.

Infection is most commonly seen in colonies of cats and multicat households, where the organism is presumably spread between cats by close and direct contact. There has been no evidence of spread from other species, or spread via food or water. In one study, 31% of cats at a cat show in the USA were identified as being infected with this organism, suggesting that this may be an important, common, and previously unrecognised cause of diarrhoea in cats.

Although most information on T foetus infection has come from studies of cats in the USA, we have identified several cases of infection in cats in the UK (mostly in young pedigree cats, and all from multicat households generally with more than one cat being affected), and it has also been identified in cats from Germany, Italy, Spain and Norway. In the UK, up to 30% of faecal samples from cats with diarrhoea are currently being found to be infected; with young pedigree cats (particularly Siamese and Bengal) being significantly more likely to be infected. The evidence therefore suggests that T foetus is probably quite widespread in cat populations, and infection is most likely where there is a high density of cats sharing the same environment.

While T foetus is known to be a significant cause of reproductive disease in cattle (infertility, abortion and endometritis), its role in causing reproductive disease in cats is still unclear. There is one report of a cat from Norway that came from a T foetus-infected household and developed pyometra (which was found to contain T foetus organisms). The cat may have been predisposed to the infection by having received six weeks of oral contraceptive (medroxyprogesterone acetate). It has also been suggested that tom cats may be able to harbour the infection in their prepuce.

Assessment of the cats faeces for the presence of T foetus can be made using a number of different methods (see below for more details); (i) looking for moving parasites in fresh faecal smears (ii) using a specific culture system or (iii) by detection of T foetus DNA using PCR. The different methods have differing sensitivities: in one study direct smears were positive in 5/36 cases, culture in 20/36, and PCR in 34/36 cases; so the PCR is by far the most sensitive test, but even this can be hampered by intermitted shedding of the parasite.

Diagnosis of T foetus infection is usually straightforward. The organism exists in the intestine as small, motile trophozoites, and these can be detected under the microscope. For optimum results, fresh faeces should be examined, and if any mucus has been passed with the faeces this is the most likely place to find the organisms. Smears of faeces/mucus diluted with some saline can be made on a microscope slide. A cover slip can be pressed over the smear and then the slide can be examined under x200 and x400 magnification. In most clinically affected cats, large numbers of the small motile organisms can be seen – they appear a little bit like microscopic tadpoles with very short tails (!), and have an undulating membrane that runs over the length of the body. Their movement is described as ‘jerky, forward motion’. Examination of multiple smears and multiple faecal samples will improve the detection of the organism. Rectal swabs can also be examined for the organism – a cotton swab can be inserted into the anus and rotated over the colonic mucosa – this is then withdrawn and a smear made on a microscope slide which is again diluted with saline and examined as above. The organism needs to be distinguished from Giardia, another protozoan parasite, but with Giardia infection the trophozoites tend to be far fewer in number, they are binucleate with a concave ventral ‘sucker’, and do not exhibit the same forward motion as T foetus. If a cat has received recent antibiotic therapy, this can suppress the number of T foetus trophozoites shed, and can make the diagnosis more difficult. In such cases, more sensitive diagnostic techniques may be preferable.

Two other diagnostic tests are available which are both more sensitive and specific for this organism. Firstly, the organism can be cultured from faecal samples using a system developed for diagnosis in cattle. The ‘In Pouchtm TF’ test (BioMed Diagnostics, Oregon, USA) uses a liquid culture system in a sterile plastic pouch. The pouch can be inoculated with 0.05g of faeces (about half the size of a small pea). The pouches are incubated at room temperature and can be examined microscopically for the motile organisms every two days for 12 days. This test is more sensitive than direct examination of faeces and helpful for detecting infections where direct smears are negative. Giardia, and other similar organisms will not grow in this specific culture medium. In the UK, this system was available from Capital Diagnostics in Edinburgh (0131 535 3145) but its high prevalence of false negatives (due to the parasite dieing in the cold UK postal system) means that it is not recommended as the PCR is far more sensitive.

The most sensitive and specific test is a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test – a sophisticated test that can detect the presence of the genetic material of the organism. This is an extremely sensitive test that is available in the UK and US from a number of laboratories (please see below).

Current information suggests the long-term prognosis for infected cats is good, and that they will eventually overcome the infection. However, this is a slow process – in one study of infected cats, resolution of the diarrhoea took an average of nine months, with occasional cats having diarrhoea persisting for more than two years, and rarely for life. It appears that most infected cats continue to shed low levels of the organism in their faeces for many months after the resolution of the diarrhoea.

Most studies on treatment of T. foetus infection in cats have been unrewarding. The organism is resistant to most traditionally used anti-protozoal drugs such as fenbendazole and metronidazole. The use of a variety of different antimicrobial drugs has been reported to improve faecal consistency during therapy of infected cats, possibly because of interaction between T. foetus and the bacteria normally present in the intestine. However, such antibiotic use is not recommended as it may ultimately prolong the shedding of the organism, and does not resolve the underlying problem.

A recent study by Dr Jody Gookin at the North Carolina State University (who has performed most of the work on this infection in cats) identified that ronidazole and tinadazole (antibiotics similar but not the same as metronidazole) may have efficacy against T. foetus infection in cats (JVIM, 2006;20:536; Am J Vet Res, 2007; 68:1085). From limited studies ronidazole appears to be more effective than tinadazole. Ronidazole appears to be relatively safe, although a small number of patients have developed neurological signs e.g. twitching and seizures, which have resolved on stopping the drug. (The neurological signs are similar to those seen in some kittens, or cats with liver disease, when they are given standard or high doses of metronidazole). However, ronidazole is not licensed for use in cats; it should only be used with caution and with informed, signed, owner consent. Initial studies suggested that a dose of 30-50mg/kg once to twice daily for two weeks is capable of both resolving clinical signs and potentially eradicating the T. foetus. However, keeping to the lower end of the dose is advisable (30mg/kg), as is giving it only once daily, and reducing it even further for young kittens or cats with hepatopathy; (10mg/kg once daily for two weeks). To ensure that each kitten receives the correct dose, and so reduce the risk of side effects, it is also important to weigh the kittens prior to ordering the reformulated capsules. The bitterness of the powder means that it must be placed in capsules prior to administration.

Ronidazole (10% powder preparation) is commonly used to treat trichomoniasis in birds (e.g. pigeons). However, it is not available in this form in the UK, and the consistency of the 10% formulation is difficult to guarantee. Therefore, we have gained permission from the Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) to use 100% pure chemical grade ronidazole to treat T. foetus infected cats. This is the form that is now used in the USA. In the UK it can be obtained upon receipt of a signed named-animal prescription as capsules from Nova Laboratories, Tel: 0116 223 0099; Fax: 0116 223 0120: email: sales@novalabs.co.uk. While the VMD have agreed to our use of this chemical in these cats, they strongly recommend that detailed records are maintained and that no cat is treated without first obtaining informed, signed, owner consent. In addition, we should compile data on all potential adverse effects: send case information on any potential adverse effects to Danielle.Gunn-Moore@ed.ac.uk.

Care should be exercised in the use of ronidazole, as there are very few studies of its use in cats, and long-term studies in other species have suggested some potential toxicity concerns. (In many countries its use in food-producing animals has been banned to minimise human exposure). Careful handling of the drug is therefore advised. It should never be given to pregnant queens (or queens about to be put to stud): it is very teratogenic and may result in a number of different and severe defects. Anyone handling ronidazole should wear gloves (especially if they are a woman of reproductive age).

Since the diarrhoea usually resolves over time, and is often more of an inconvenience than being associated with significant adverse effects in affected cats, it may not be necessary or advisable to treat all affected cats with ronidazole. Using a simple highly digestible diet or a high fibre diet may result in improved faecal consistency, and this may be sufficient to control the clinical signs in some cats.

Although not proven, it is thought that T. foetus may be able to infect humans; as a precaution people in contact with infected cats are advised to take basic hygiene precautions to avoid ingesting the parasite. These precautions will also help to prevent the spread of the infection to other cats, and prevent humans from being infected with other infections that the cat may carry.

Suitable hygiene precautions include:

- Washing hands thoroughly after handling cat faeces

- Washing hands thoroughly after cleaning cat litter trays, whether the cat has diarrhoea or not

- Cat scratches or bites should always be washed immediately with soap and water. Seek medical attention as soon as possible if signs of infection appear, such as redness, pain or swelling.

- Persons with a weakened immune system should not handle their cat’s faeces or litter box, they are advised to wash their hands after handling their cats, and they are advised not to keep cats that have persistent diarrhoea. If their cat develop diarrhoea it should be fully investigated and if found to be infected with Tritrichomonas foetus it should be treated with ronidazole and then re-tested, or (at least temporarily) re-homed until the infection has resolved.

For further information on T. foetus infection in cats: www.fabcats.org. For veterinary surgeons seeking further discussion, contact Danièlle Gunn-Moore: Email: Danielle.Gunn-Moore@ed.ac.uk. Tel: 44 (0)131 650 7650 Fax: 44 (0)131 650 7652.

In the UK this is available from Capital Diagnostics, SAC Veterinary Science Division, Bush Estate, Penicuik, Midlothian, EH26 0QE: Tel. 0131 535 3145). Alternatively, a real-time quantitative PCR (QPCR) assay is now available, which incorporates an internal amplification control so that false negative results are avoided. The assay is performed on a small volume of faeces (2-5ml) at a cost of £29 (+VAT); further details on the test and submission forms can be found on http://www.langfordvets.co.uk/lab_pcrnews.htm or by contacting Langford Veterinary Services Diagnostic Laboratories at the University of Bristol, Langford House, Langford, Bristol, BS40 5DU. Tel: +44 (0)117 928 9412 Fax: +44 (0)117 928 9613 Email: lvs@langfordvets.co.uk.

In the US samples can be submitted to the College of Veterinary Medicine, North Caroline State University (USA) for this test – information on this is available at: www.cvm.ncsu.edu/mbs/gookin_jody.htm.

Thanks to Dr Andy Sparkes, Ellie Mardell and Kirsty Wood who were involved with the initial preparation of this paper.

Dahlgren SS, Gjerde B, Pettersen HY (2007) First record of natural Tritrichomonas foetus infection of the feline uterus. Journal of Small Animal Practice 48:654-657

Foster DM, Gookin JL, Poore MF, Stebbins ME, Levy MG (2004) Outcome of cats with diarrhoea and Tritrichomonas foetus infection. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225:888-892

Gookin JL, Breitschwerdt EB, Levy MG, Gager RB (1999) Diarrhoea associated with trichomoniasis in cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 215:1450-1454

Gookin JL, Birkenheuer AJ, Breitschwerdt EB, Levy MG (2002) Single-tube nested PCR for detection of Tritrichomonas foetus in feline faeces. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 40:4126-4130

Gookin JL, Copple CN, Papich MG, Poore MW, Stauffer SH, Birkenheuer AJ, Twedt DC, Levy M (2006) Efficacy of ronidazole for treatment of feline Tritrichomonas foetus infection. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 20: 536-543

Gookin JL, Foster DM, Poore MF, Stebbins ME, Levy MG (2003b) Use of a commercially available culture system for diagnosis of Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 222:1376-1379

Gookin JL, Levy MG, Law JM, Papich MG, Poore MF, Breitschwerdt EB (2001) Experimental infection of cats with Tritrichomonas foetus. American Journal of Veterinary Research 62:1690-1697

Gookin JL, Stebbins ME, Adams E, Burlone K, Fulton M, Hochel R, Talaat M, Poore M, Levy MG (2003a) Prevalence and risk of T foetus infection in cattery cats (Abstract). Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 17:380

Gookin JL, Stebbins ME, Hunt E, Bulone K, Fulton M, Hochel R, Talaat M, Poore M, Levy MG (2004) Prevalence and risk factors for feline Tritrichomonas foetus and Giardia infection. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 42:2707-2710

Gookin JL, Stauffer SH, Coccaro MR, Poore MF, Levy MG, Papich MG (2007) Efficacy of tinidazole for treatment of cats experimentally infected with Tritrichomonas foetus. Am J Vet Res 68(10):1085-8.

Gunn-Moore, DA, McCann, TM, Reed, N, Simpson, KE, Tennant, B. (2007) Prevalence of Tritrichomonas foetus infection in cats with diarrhoea in the UK. JFMS 9: 214-218

Gunn-Moore DA, Tennant B. (2007) Tritrichomonas foetus in cats in the UK. Vet Rec. 160(24): 850-851

Kather EJ, Marks SL, Kass PH. (2007) Determination of the in vitro susceptibility of feline tritrichomonas foetus to 5 antimicrobial agents. J Vet Intern Med.;21(5):966-70)

Levy MG, Gookin JL, Poore M, Birkenheuer AJ, Dykstra MJ, Litaker RW (2003) Tritrichomonas foetus and not Pentatrichomonas hominis is the etiologic agent of feline trichomonal diarrhoea. Journal of Parasitology 89:99-104

Mardell EJ, Sparkes AH. (2006) Chronic diarrhoea associated with Tritrichomanas foetus infection in a British cat. Veterinary Record 158,765-766

Romatowski J (2000) Pentatrichomonas hominis infection in four kittens. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 216:1270-1272

Rosado TW, Specht A, Marks SL. (2007) Neurotoxicosis in 4 cats receiving ronidazole. J Vet Intern Med 21(2):328-31

SAC (SAC Veterinary Services) Monthly Report (2007); available online www.sac.ac.uk/consultancy/veterinary/publications/monthlyreports/2007 : Veterinary Record 161(16): 544-546

May 2009

Figure 1: Rectal smears can be made using cotton

swabs rolled over the rectal wall. Smears can be made on glass slides,

and material obtained should be diluted with saline to prevent desiccation.

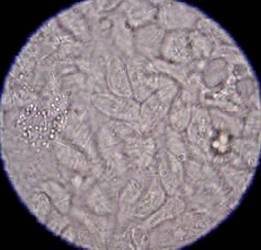

Figure 2: Typical appearance of a large number of T foetus

organisms in a faecal smear under x400 magnification. When examined,

the organisms can be seen to be highly motile.

Figure 3: Appearance of an individual T foetus

organism stained with Lugol's iodine. Three anterior flagellae can

be seen, and an undulating membrane runs the length of the body.

Detailed

information is published on the Feline Advisory Bureau website and

can be accessed via the link below:

http://www.fabcats.org/breeders/inherited_problems

There has been a great deal of news in the press recently about cats being poisoned by antifreeze, both maliciously and accidentally. A spate of publicised incidents was reported in the Somerset area, but then seemed quickly to spread to other areas of the country. As with any such event, it is difficult to determine whether the spread of cases was due to copycat poisonings, or simply because the increased publicity increased reporting of more suspected incidents. One hopes the latter. Nevertheless, antifreeze products can pose a serious threat to companion animals. Antifreeze is reportedly very sweet to taste and presumably palatable, and poisonings in dogs are quite common. Cats are at great risk as the fatal dose for ethylene glycol based antifreezes in cats is about 1.5ml per kg bodyweight, so cats only need to consume about five to six ml – a couple of good licks – to be in immediate and life-threatening trouble. For successful management, intervention must be extremely fast as glycols are readily and rapidly absorbed, with the kidney function becoming rapidly impaired. There are cases of fatality occurring within hours of ingestion. One of the antidotes available for such poisonings is not tolerated by cats at all, so the only therapy left is giving ethanol (alcohol), so it is very difficult to treat.

There are suggestions that the poisonings could be accidental with the cat drinking from a water feature which has had antifreeze added to stop it freezing up over winter. However, most of these poisonings seem to have happened before the bad weather and only water features without fish or pond life could be treated in this way, as alcohols and glycols permeate fish membranes easily and will affect them.

Between 2003 and 2007, the Veterinary Poisons Information Service (VPIS) documented 108 antifreeze-related enquiries in cats and 100 in dogs overall – so about 20 cases per annum. 46 of the feline cases and 35 of the canine cases were followed up. Of these, 30 of the feline cases were known to have fatal outcomes (65.2%) compared with eight known fatal outcomes in dogs (22.9%). Higher mortality rates have been reported in other published studies from elsewhere. It is sad to report that 2008 was a particularly bad year. Up to the end of October, 93 cases had been reported to VPIS ( London ) – 56 in cats and 37 in dogs. Usually the number of reports rises in the months for October to March, so these numbers are worryingly elevated. Case outcome data is not available for all these cases yet – but 12 deaths have been reported in cats from 16 returned case follow-up questionnaires (75% mortality therefore).

The message for cat lovers is to make sure that there is no spillage of antifreeze in garages or sheds or under the car. The fastidious clean cat will groom it off feet if it is walked through. Collectively, we must ensure that the message gets out that these chemicals are very dangerous for pets and the Cat Group, along with VPIS, will be raising the issue in the press in the future.

The SPCA in British Columbia , Canada , has produced a helpful manual and DVD for those working in rescue situations, called Catsense™ - the Emotional Life of Cats.

The Catsense™ manual is a complete guide to putting in place a system for good welfare of cats in a shelter environment. It includes information on housing, behaviour, checklists for stress, and planning to put in place good evidence-based welfare practices.

The DVD explains the emotional states experienced by cats in shelters and shows examples of cats displaying anxiety, fear, frustration and depression.

A two hour training DVD, presented by Nadine Gourkow, advises on intervention strategies and procedures to improve welfare for cats.

More information about these training aids, and a clever ‘hide, perch and go’ box can be found on www.spca.bc.ca/hideperchgo

|